In August 1967 blistering heat bore into Hanoi’s Hoa Lo prison. I was entering my second day on the concrete floor of the bath stall as the morning haze gradually dissolved into the first blue sky I had seen in more than a month.

The heavy iron bar of the leg irons pressed against my ankles. Tight wrist manacles pinned my arms behind my back leaving me lying in an awkward position. Even in the uncertainty of what was about to happen, I felt a relief in the fact that the guard had not bothered to check on me in several hours.

“Tap Tap Ta-Tap Tap.” I heard the familiar shave-and-a-haircut call-up. I couldn’t tell where it came from. “Got to be careful — no way to clear for guards in this situation.” I managed to roll over on one side and with some difficulty rapped a crisp double tap with my knuckles on the bathhouse floor. The message reverberated through the wall and floor, barely loud enough to distinguish. “JL HERE – WHO U?”

The tapping was even and easy to read, obviously an old timer. “JL . . . JL . . ,?” I thought. “Oh! Jim Lamar, what’s he doing over there?”

I answered. “DG – HI JL – WHAT’S UP?” The tapped reply rang back, “THE V R MAD – HEAT IS ON JS (Jim Stockdale) MANY TORTURED TO REVEAL PW ORGANIZATION – R U OK?”

Things had been extremely grim through August, especially since the evening of the 21st when the Desert Inn cell block had erupted as shouts of torture rang up and down the hall over a beating and rope torture incident which began in a room with Ron Storz, Wes Schierman, Orson Swindle, and George McKnight. So now, the V were on a camp-wide rampage aimed at destroying our covert organization and organized resistance, specifically aimed at destroying senior officer authority.

“I’M FINE,” I tapped back. “HOW U?”

“OK – KEEP UP GOOD WORK – GBU (God bless you).” I started to reply, but hearing the guard’s footsteps approach, I rolled sideways and banged the irons against the floor to sound the alarm and cut it off. With a rifle slung over his shoulder, the guard entered the bath stall and gave me a kick in the ribs. “Ghi, (my Vietnamese pseudonym) up.”

“Sure”, I thought. “I’m supposed to ignore 20 pounds of paraphernalia weighting me down and jump right up.” The turnkey entered behind him and opened the lock on the stocks and manacles. It took a few minutes to get enough circulation going in my feet and arms to steady myself enough to follow. As it turned out, I was only going a few yards away to the Riviera, a building consisting of several small interrogation rooms. My heart dropped at what I saw as I entered the room: a complete assortment of straps, ropes, wires, iron bars, and bloody rags. I was placed in a kneeling position and again fitted with leg irons and manacles. The six- foot-Iong, one-inch-diameter iron bar would ensure that I would not find a comfortable position while I was being prepared for the next act of this gruesome performance. I prayed for those who had gone through this room earlier and for strength, courage, and endurance to face what-ever was about to happen.

* * *

The guard returned that afternoon and marched me through a passageway and across an alleyway to a large room just out-side of the Little Vegas area of Hoa Lo. I knew it from others’ description as Cat’s quiz room. The guard nudged me with the barrel of his rifle and pointed to the center of the room. “Knee don!” I took my position standing on my knees while the guard took his station, waiting in the corner behind me. The room was bare except for the ever-present table with a blue cloth draped over it. Behind the table, there was another ominous pile of assorted ropes, irons, and straps. After a wait of about I5 minutes, the interrogator, “Greasy,” strode into the room with a flourish and began pacing back and forth in front of me. Needless to say, I was feeling quite uneasy. Greasy was totally unpredictable and possessed a cunning cruelty which he had obviously taken great pains to develop. I was never sure whether his act was meant to impress me, the guard, or if it was only for his own narcissistic benefit. He paused in front of me and turned up his nose, nodding toward the ceiling. A slight sneer spread across his face as he slowly began. “How do you like the air? Yes, in this room, it has some air with it. How do you like the air?”

“Air, atmosphere, feeling, character?” I thought. “Oh,” I said, “It’s all right.”

“And so, before, you live with Sta’dale?”

“Yes.”

“He is much older than you.” (He was pacing again now, sometimes walking behind me.) “What did he tell you?”

“Well, we talked mostly about home and things we liked to do with our family…”

“NO!” He shouted. “About the camp. What were his orders?”

“Uh, well, you see, we think alike, and we are of the same mind, so there was no need for any orders.”

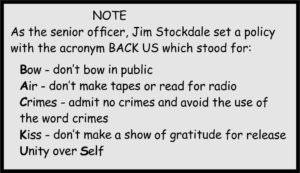

He came around quickly with his foot, catching me just under my ribs on the right side of my back. I shifted my weight trying to maintain my balance. “You want to be diehard‘? You are stupid. Other criminals cooperate with us. We know all about Sta’dale’s policies. We know about BACK US.”

He came around quickly with his foot, catching me just under my ribs on the right side of my back. I shifted my weight trying to maintain my balance. “You want to be diehard‘? You are stupid. Other criminals cooperate with us. We know all about Sta’dale’s policies. We know about BACK US.”

* * *

Blindfolded, I was carefully trying to keep track of distances and turns as the turnkey guard, “Useless,” led me around the corner of the building and into a narrow doorway which had to be the Stardust cell block. Behind one of the heavy wooden doors, the slow deliberate sound of someone clearing his throat acknowledged my presence. I coughed twice in reply. The rifle barrel behind me responded with a sharp nudge between my shoulder blades. I bumped clumsily against the walls as I was led to the left and then to the last door on the right, Stardust No. 8.

The room was so narrow, the bed board protruded into the doorway and left barely enough space to stand between the double high bunk and the wall. “Si don!” Useless pushed me onto the lower bunk, and placed my ankles into the stocks which were built into each bed board. He locked my feet in place with the heavy iron bar, checked the security of my blindfold and the wrist manacles behind my back, and backed out of the cell.

The movement of the heavy rusted hinges, the impact of the wood and metal door against the plastered clay tile and concrete wall, the slamming of the bolt and lock, and the retreating flip-flop of tire-tread sandals echoed up and down the cell block and then gradually faded into the hollow silence of solitary confinement.

After eight months in Hanoi, deprivation, intimidation, and isolation were no easier to accept. I pushed back the blanket and mosquito net rolled up beside me, twisted my feet side-ways in the stocks, and attempted to find a position which would get me through the night. The mosquitoes would have a feast.

* * *

I could hear Useless’s distinctive walk as he entered the cell block about mid-morning, humming the Viet Cong fight song. He began opening cells one by one at the other end of the building yelling “Bo.” This single command indicated that the occupants, ready with bucket, soap, and cup in hand would have about 10 minutes in the bathhouse to empty their waste, wash bodies and clothes, and perhaps shave before returning to a dirty cell and an uncertainty as to when the opportunity would again present itself.

I was unsure about what to expect when he reached my door. I sat up as the door was unlocked. Useless filled the small pitcher at my feet with drinking water, and placed my waste bucket in the hall for someone else to empty. I was about to decide that I had become invisible when Useless came in and stood next to me. I could just see through a slit at the bottom right side of my blindfold, which had loosened a bit during the night. Useless carefully tore a new Trong Son cigarette squarely in the middle, throwing half on the floor and placing the other half into my very surprised lips.

“Light!” I drew in a mouthful of smoke as he lit the end of it and left. I contemplated the irony of the situation as I puffed a few more times and then let it fall on the floor. I hadn’t paid much attention when Greasy had said my punishment would include losing half my cigarette allowance. Now, I pondered the sanity of a world in which necessities of life are denied, but half a cigarette is dutifully given to a trussed up, blindfolded, former non-smoker three times a day.

At noon, my blindfold and wrist cuffs were removed while I ate rice and boiled weeds. I took the opportunity to arrange my blanket and mosquito net so that they could be used to help me get some sleep.

When Useless returned for the tin plate, he carefully replaced the blindfold and manacles, leaving me again to face the extended boredom and discomfort. Occasionally, the silence would be broken as the roving guard opened and slammed the small peephole door with the warning, “Kip salent!”

Gradually, activity in the prison ceased as the Vietnamese took advantage of their traditional siesta time. Retreating to the sanctity of my thoughts, I reviewed my memory bank of information picked up since captivity, including names of the other prisoners, who is in each cell, information about other POW camps, and then, on to less serious but more interesting pastimes like trying to picture every girl I’ve ever known from the first grade on.

I was just into my sophomore year in college wondering whatever happened to crazy Margaret when I heard a hoarse whisper, “Hey, G.I.” I wasn’t sure I heard that, and I thought, “Is this a guard trying to trick me into answering so they could bring on the ropes?”

“Hey, G.I.”

No, that voice was distinctly American. “What did he mean, ‘G.I.?’ What war was this guy from, anyway?”

I answered “Yeah, go ahead.”

“This is Scotty Morgan,” he whispered. “There’s a hole in the back wall between our rooms I can talk through. I’m in Stardust 7 with Tom Sima. He ’ s clearing the hall under the door while we talk. What’s your name?”

I gave him my background: aircraft, service, rank, shoot down date, home state, etc. He continued, “We’re both Air Force captains. I’m 33 and Tom’s 34 years old, both single and shot down in ’65. It’s risky to talk loud, but we will contact you each day during siesta. When you get out of leg irons, we can do some serious talking. We think the V will remove your irons on September 2. That’s their national day. Hang in there. God bless.”

“Thanks. God bless you both.” Two years, I thought, how depressing to be old, single, and in here.

* * *

Scotty was right. September 2 brought a trip to the bath house, a shave, and a better-than-average meal. Threats, harassment, and long hours of isolation continued, but thanks to the hole at the back of the room and Tom clearing the Stardust hallway, my conversations through the wall with Scotty covered every conceivable subject.

By mid-October we were getting desperate, trying to remember punch lines we had heard in grade school as we exchanged the “joke of the day.” We discussed the particularly nasty summer, the heavy bombing raids, increased numbers of prisoners, and the desperation exhibited by the actions of the Vietnamese. We still worried about how the purge to eliminate senior officer authority would play itself out. Jim Stockdale was absent from our current communications network, and we didn’t know what had become of Storz, Schierman, Swindle, and McKnight.

On Sunday, our second meal was over early. Useless had checked the locks on all the cells and had left the area. At first, I thought I was overhearing another tapped conversation at the other end of Stardust, but I soon realized that someone was trying to tap from the large room that adjoined the back side of the Stardust building. We called it the Tet room since decorating it to celebrate the Chinese New Year seemed to be one of its primary uses. I hoped the roving guard was someplace else. By placing my ear against the door jamb, I could only clear about three feet down the hall through the crack at the bottom of the guard’s peephole. I acknowledged with two taps and waited to see who might be on the other side of the wall. A methodical pattern of taps spelled out the name, “RON STORZ.”

I answered, “DAN GLENN IN SD 8–R U LIVING IN QZ RM?”

“YES, FOR NOW–AM TIED TO BED BOARD 24 HRS PER DAY.”

I acknowledged each word with a rapid double tap. The speed gradually increased as we each tuned into the rhythm of the other. “I’VE BEEN UNTIED FOR CHOW—THIS IS FIRST TIME GUARD HAS LEFT ME ALONE UNTIED—I THINK HE’LL BE BACK IN ABOUT 10 MIN—I’LL TRY TO CONTACT U EACH DAY IF THIS CONTINUES.”

There were so many questions I wanted to ask this Air Force captain. Ron was the first person to talk to me under the door in my early days in the T-bird cell block. Highly regarded by everyone who had lived near him, his persistent resistance to our Vietnamese captors and his resourceful dedication to keeping POW communications alive were legendary. I went on: “CONCERNED ABOUT YOUR TREATMENT SINCE 21 AUG—R U OK?”

I could feel his pain coming through the wall as he answered. “I THINK SO—THE V BROKE SOME RIBS, AND I’VE LOST SOME BLOOD–I THINK THINGS HAVE CALMED A BIT NOW.”

After passing some information on who was in Stardust and arranging some signals for contact the next day, we signed off. I was excited about getting into contact with Ron but deeply disturbed knowing that things were not going well for him.

As soon as we got a chance to talk through the rat hole the next day, I told Scotty the news about Ron. He said he and Tom could clear for me, making it relatively safe from the roving guard and easier to tap to Ron. Ron and I had a very short tapping session each of the next two days. We exchanged some news about what had happened in the past two months. I thought I could detect a little improvement in his spirits.

On Wednesday, his call came so late that I was concerned about being able to clear. In the evening, the guards were less predictable, and the dimmer light made seeing more difficult through the limited vision afforded by the cracks around our doors.

He started to explain why he was late. “ACTIVITY IN COURTYARD.” Then, he thumped the wall with his elbow as a danger signal. I was secure, knowing that Scotty and Tom were clearing behind me, so I continued to listen at the wall. I could hear the door to the Tet room open and the muffled sound of someone entering the room.

I waited, hoping we would get a chance to tap again. I heard the door close, and after a short time, Ron came back on the wall and quickly tapped, “GUARD TOLD ME TO ROLL UP–I’M MOVING.”

I responded excitedly, “I HOPE TO SEE YOU SOON–GBU.”

“RR (roger, roger) GBU.” He answered and thumped the wall and moved away just in time before the guard returned. I could hear something being moved around the room kind of like straightening the furniture, and then, the room was empty.

* * *

“Wedge,” an overeager, under intelligent roving guard, banged his rifle butt on the door and opened the peephole for the third time in the last five minutes. Wrinkling his brow in a contemptuous squint, he grunted, “Huh?” Engaged in a contest of stares, I slowly swung my feet around to stand up. Glaring, he hissed, “Su My” (rough translation, “dirty American”) and slammed the cover on the peephole.

The late evening of this unusually nondescript Friday seemed interminably long. None of my normal mind diversions would take the edge off a slump into a mood of loneliness and uncertainty. I was arranging my mosquito net as the gong finally sounded, signaling it was time to sleep.

Wham! The quiet was broken with such suddenness I jerked, bumping my head on the upper bunk. Wedge was back. He tapped his fist on the door. “Huh?” He tapped again. “Huh, huh?” He jumped in front of cell No. 7’s door and repeated the accusations to Scotty and Tom.

I crawled under my net to await the inevitable confrontation which would follow. Since I had spent the day in Cat’s quiz room with Greasy two months ago, I lived in fear that he would follow through on his many threats. The prison forces were experts at taking advantage of physical weakness, but what they were really looking for was a tiny flaw or weakness of character which they could eagerly exploit.

My game plan, developed shortly after arrival in Hanoi during my initiation into the communist torture for propaganda program, was simple: maintain faith in the principles, people, and country I believed in when I was shot down and, despite complete disregard here for human rights, conduct myself, as much as possible, as a naval officer in a POW situation, with all the dignity and honor I could muster. I knew from experience this was not an easy task. I also knew, thanks in part to many discussions with Jim Stockdale when I had lived with him, that only through unity would we be able to win any battles with our captors.

It only took a few minutes for Useless to return to escort me roughly to the Riviera quiz room with the help of an enthusiastic Wedge. I was surprised at Greasy’s mood when he came in. He was showing off as usual but appeared to be gloating over what he must have thought was increased control over the American prisoners.

“I am very tired with you,” he said. “Why you communicate with other criminals? You want to live in dark place?” I got the impression the trumped-up tapping charge was just so he could rant to someone.

“Just like before,” I paused, trying to keep my voice as calm as possible, “your guard made a mistake.”

“How long since you live with Sta’dale?”

“About five months.”

“And now, he lives in another place. He bows to the will of the Viet’mese people and does not resist.”

“In your dreams,” I thought. “I don’t think so,” I said.

After a 15-minute tirade on Vietnam, one country fighting on to final victory no matter how long it takes, etc., etc., he waved his arm toward the door. “I allow you to be punished. Think seriously about your actions. Go back your room.”

It’s funny how the next morning I took a chance to quickly tap to Scotty, confirming he and Tom were also in leg—irons, accused of tapping on the wall, which of course, we hadn’t, until now. The long day became longer. During siesta time, I really missed the daily enlivenment I had begun to rely on from the conversations through the wall. There were many times in the past when the physical misery had been much worse, but now I seemed to be spiraling into a worsening state of depression. I was dwelling on what seemed at the time a hopeless situation.

With my legs locked horizontally in the irons, I sat hunched, staring blankly at a spot on the floor near the crack under the door. Suddenly, accompanied by a rapid cadence of continuous high squeaks, a tiny mouse marched double-time into my view. I watched in amazement as he continued, one squeak for each step he took. The mouse was exactly what you would have if you combined the squeak from a rubber toy mouse with the precision movement of a Swiss clock. He made several circles about a foot in diameter without missing a beat.

Then, upon reaching the wall, to my total astonishment, he marched up the vertical surface as easily as he negotiated the floor. After making a couple of tight circles on the wall, he returned to the floor and went out the door. I laughed out loud as he left as quickly as he had appeared, taking my depression out the door with him.

I spent the rest of the day musing about my surprise visitor. I thought about the Scottish king, Robert Bruce, and how in his solitude, he was inspired by a courageous spider that showed him the value of perseverance. But what message was I supposed to get from this crazy robot mouse? Was it to keep on trucking, one step at a time? Maybe he was checking to see if I had some direction for him. Perhaps the message was within me, and the mouse was simply there as a catalyst to awaken me to it.

The little squeaker came back two more times, and then, I guess he had other places to go.

In three days, I was out of leg irons again. In early November, I would move back to the Desert Inn cell block with two roommates. Over the next five and a half years, I would move many more times, sometimes living with more and sometimes fewer American servicemen cellmates. They had all dealt with the collective experience of the Vietnamese prison system. Each one I met rose to the occasion and fought back in his own unique way against the North Vietnamese program of propaganda extortion.

We don’t always know how we touch the lives of others. Sometimes very different lives cross paths in unusual ways. Each crossing can be an opportunity to be there for someone else and discover our greater self within as we walk for a time along the path with another.

Jim Lamar, Scotty Morgan, Ron Storz, and, of course, Jim Stockdale were there for me, and I hope, in some way, I was there for them. I never got to meet Scotty Morgan or Jim Lamar face to face until we came home. Ron was kept solo and died in captivity, but I still sometimes tap a short message to him in the quiet of the evening.