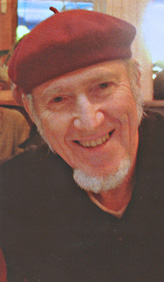

Herb Greene

“There is urgency in coming to see the world as a web of interrelated processes of which we are integral parts, so that all of our choices and actions have consequences for the world around us.”

Alfred North Whitehead

Yesterday, Herb Greene reminded me of the role architectural education played in shaping my time in Hanoi’s prison. He talked to an audience of students, professors and others in the university community about his education, teaching and work while at the University of Oklahoma. He spoke of how he was influenced by the genius of his mentor, Bruce Goff and how he found inspiration in the writings of Alfred North Whitehead.

Yesterday, Herb Greene reminded me of the role architectural education played in shaping my time in Hanoi’s prison. He talked to an audience of students, professors and others in the university community about his education, teaching and work while at the University of Oklahoma. He spoke of how he was influenced by the genius of his mentor, Bruce Goff and how he found inspiration in the writings of Alfred North Whitehead.

He was 29 years old when he waltzed into my first architecture design course in tennis shoes, jeans and a tee shirt, looking more like a student than some other professors in three-piece charcoal suits. He slapped open a large book of paintings on the drafting table next to mine and began pointing out the subtle genius of the impressionist painter’s skill in directing the feelings of the observer. That was always his teaching method; to bring you to feel the essence of design, rather than try to describe it in words.

I occasionally caught a glimpse of his latest painting while walking by the open door of his office. Across the room, chin in hand, with wrinkled brow he puzzled over the next burst of color to be applied.

One afternoon in second semester design lab, my classmates shoved tee-squares and triangles, frantically applying lines to a drawing while I stared at the blank tracing paper in front of me. Herb walked up next to my drawing table and asked what my idea was on the latest design assignment. I told him I was having a bit of trouble coming up with a concept. He pursed his lips, folded his arms across his chest and rocked back and forth while gazing into the distance out the window. I waited, not sure if I was about to receive reprimand or motivation.

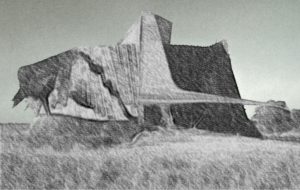

“I’ve been working on a design for my house,” he said. “Something about it wasn’t quite right. But last night I began drawing and it started to take shape.”

He picked up my 2B pencil and began to draw on the edge of my paper. “So, I made this sketch.” Tight strokes of graphite went first one way and then another creating a solid textured shape about an inch high and two inches wide. Interesting, yes, but did I see a house? No. When he finished, he studied it for a minute and then walked away.

I wish I would have saved his tiny drawing; I would like to have it framed. When he built the “Prairie House” two years later, the house that made him famous, I was shocked. It looked exactly like that assemblage of scribbles he shared with me that day.

When I found myself alone in a dark room seven years later Herb Greene had taught me something about how to use the creative potential of the mind.

he low grey overcast and quiet mist created a sanctuary for our mixed congregation. Joe offered up a prayer for those who died in the battle and healing for those who remained. With a vial of holy water brought from home he consecrated the site in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

he low grey overcast and quiet mist created a sanctuary for our mixed congregation. Joe offered up a prayer for those who died in the battle and healing for those who remained. With a vial of holy water brought from home he consecrated the site in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.